Art/Auctions Upcoming

T R E N D L I N E S I N T H E A R T M A R K E T

Last-Chance Syndrome Brings Record Prices for Some Old Masters

By Souren Melikian, The New York Times

Published: January 31, 2013

NEW YORK — In a sale of striking contrasts, sensational world records were set for some Old Masters, while abrupt failure hit others in Christie’s traditional winter auction of Old Master paintings on Jan 31.

Christie’s

‘‘Madonna and Child’’ by Fra Bartolommeo reached $12.9 million after sustained bidding at Christie’s winter auction of Old Masters in New York.

The two winners that stand out are Renaissance artists whose work has all but vanished from the market.

Fra Bartolommeo’s “Madonna and Child” became the most expensive picture ever, at $12.9 million, by the artist after bidding that involved contenders in the room and others on the phone to Christie’s agents. The sheer beauty of the circular panel still in its original frame, together with its exceptional state of preservation, placed it in the rarified category of works for which any price is conceivable as long as your budget allows it.

Add Chardin’s admirable but tiny “Embroiderer,” only 19 centimeters by 16.5 centimeters, which brought a stupendous $4 million, and few will doubt that the last-chance syndrome is working wonders in a market where masterpieces are few and far between.

But there is another side to the coin in a market where supplies are shrinking. While the very rarest and finest is pounced upon, some very good paintings easily get ignored. The overall price level has now been raised to such heights that many of the collectors who have not already lost interest in Old Masters because of the difficulty of finding great works are effectively being priced out.

As a result, pictures that do not trigger mad competition between international institutions or a few billionaires fare unpredictably.

Decision to close firm a sign of the times, says Julian Agnew

12 February 2013

Written by Anna Brady

Mayfair gallery Agnew’s, the 195-year-old family business best known for Old Masters, will close on April 30 after exhibiting for the last time at ‘The European Fine Art Fair’ in Maastricht next month.

Julian Agnew, the sixth generation chairman of the firm, told ATG: “We are neither the Tesco’s of the market like the big auction houses nor a small dealer with only an assistant and a dog who can run on very low overheads. We’re in the middle market, which is very difficult.

“Changes in the market and technology make a gallery no longer necessary unless perhaps you are a big Contemporary art business.”

Once a major force in the Old Master market, the gallery’s fortunes have faltered in recent years in a changed marketplace. In 2008, Agnew’s Bond Street premises, purpose-built by Julian Agnew’s great great grandfather Sir William Agnew in 1877, were sold for a reported £25m and the gallery announced its intention to downsize its Old Master department to concentrate more on Modern and Contemporary art at the new Albemarle Street space.

The “entirely voluntary” decision to close the gallery was taken by the 16 family shareholders, only two of whom, Julian Agnew and Christopher Kingzett, still work at the firm. The business is not in debt and, as there are still 12 years left on the lease for the Albemarle Street gallery, they are looking to assign the lease.

“It’s the correct decision, although tinged with sadness,” said Mr Agnew. “But better to recognise that the marketplace has changed than drag on in a miasma of gloom. I’m 70 and I want to have a quieter life. I will continue to look after 20-25 of my best clients, both buying and selling, until they or I stop or die! But these habits die hard and I love looking at works of art so I will continue to keep a close eye on the market.”

Talks to sell the company fell through last year and the firm has since been running down both stock and staff gradually, leaving only six employees now, including Mr Kingzett and Mr Agnew.

Mr Kingzett has not yet decided what to do next, but Mr Agnew said he plans to continue dealing.

Changing Marketplace

“It used to be that the auction houses were the wholesalers and we dealers were the retailers. But now they offer everything we can offer including privacy thanks to their private treaty departments,” said Mr Agnew.

“I think all dealers are undercapitalised for today’s market of multi-million-pound lots,” he added. “If you don’t think a model of business is working any more, the best thing to do is acknowledge it. We can now give the shareholders money to go on and spend on new businesses, or do as George Best did and spend it on wine and women!”

The increasingly short supply of good quality stock within the Old Masters market has also contributed to the decision to call it a day: “I don’t want to deal in secondary Old Masters,” said Mr Agnew, speculating that some of his Old Master dealing contemporaries may soon follow him into retirement and that few younger dealers are entering the field.

His daughter, Gina left the gallery last year and started her own Contemporary art business, so the seventh generation is keeping the family name going in the industry, albeit in a different guise.

Although stock has been run down, Agnew’s have secured some good items on consignment for their final TEFAF.

A Feeling the End Is Coming for Big Sales of Old Masters

By Souren Melikian, The New York Times

Published: February 1, 2013

NEW YORK — Slowly, the signs are multiplying that the auction market for Old Master paintings as a financially viable system might be drawing to a close.

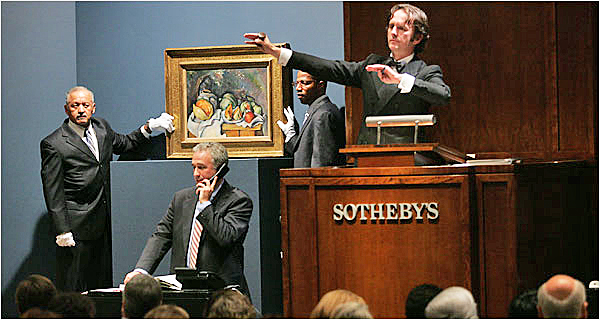

Sotheby’s

An important Flemish painting recently discovered, ‘‘Christ Blessing,’’ by Hans Memling, reached a record for the artist of $4.11 million at Sotheby’s, underlining the feverish search for Old Master paintings of undisputed authorship.

In five to 10 years, there probably won’t be enough top- to middle-range pictures left to keep the two international auction houses’ engines running.

The auction of “Property from the estate of Giancarlo Baroni,” with which Sotheby’s opened Jan 29-30 to start the winter round of Old Master paintings sales, must have given old-timers the irresistible feeling that the curtain is falling on an era when the seemingly endless abundance of pictures made the game a pure lark to large numbers of players.

Steep prices for beautiful works to which names are attached on the basis of stylistic inference, not to say speculation, are typical of a market where great works signed or documented since Day One are vanishing fast.